WHEN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY AND I WERE YOUNG

The following is a memoir written by Evelyn Lorene (Lorraine) Cochrane Mains for her grandchildren in 1964 to cap a summer of shared adventures in Anchor Valley, north of Hillman, MI. She relates a number of adventures with some entertaining drawings by Carole Mains Finley, and it was typed by another daughter Barbara Mains Maldegan. From what I have seen, it was printed up using an old mimeograph, so many of the drawings in the photocopy I obtained from Frances Buckmaster, Eunice Waisanen's daughter and Charlie Herron's granddaughter, have spots in them. I scanned the pictures and cleaned them up. In addition, several of the drawings appeared to have become faint in the mimeo process, so I "enhanced" them with a bit of editing to sharpen some lines that were disappearing. I hope I didn't ruin anything. This set of writings is really a sort of folk art, I think. Mrs. Mains did have a state-of-the-art education for 1920 and she was aware of literary currents in in America, but in these family memory works she comes across as an original, unpretentious voice who is working with some pretty difficult techniques to give a personal audience a bit of memory to carry forward. I think it warrants preservation for its family value and its artistic content. I hope that whatever I have added is in the same vein. This is a rather long piece so I have prepared a Table of Contents of hot links to the section headers that appear in the original. Unfortunately, I have not put in links yet to take the reader back to the top. Perhaps later. This has taken me about five months to get together. Oh yes, before I forget, again, I would like to thank Myra Herron, daughter of Harlo Herron and granddaughter of Fred Herron for proof-reading the text some time ago. She has provided invaluable help and I hope to publish the pile of photos she has forwarded to me. Nelson Herron, Labor Day, 2004

The other pieces of her work that I have put on the web so far include: Saga

of an Alpena Pioneer Family, The

Story of Catherine Link Herron (Clark), I

Remember Grandma Too, The

Early Life of Estella Jane Herron, The

Story of Henry Cochrane,, and The Story the Link Family. ,

Isn't it startling to think that the place in which we are born, the time in which we are born and the family to which we are born start to make us the person we become. For all these reasons no two persons in the world are alike. I often wonder what group of circumstances happen to make a truly great man or woman. The events that are shaping you are different from the life I led as a child. Would you like to know some of the things that happened when this twentieth century and I were young?

I was born November 3, 1901. My grandmother and a midwife, Grandma Smith, were on hand to see to my arrival. I was born at noon on Sunday. My mother decided if she ever had any more children she would go to town and have a doctor and something to ease the birth.

My father evidently thought I was perfect. What to name such a lovely child? My mother submitted a list of names - all discarded. A current novel had a heroine by the name of Lorene. My father decided on Evelyn Lorene. I was called Lorene and never nicknamed.

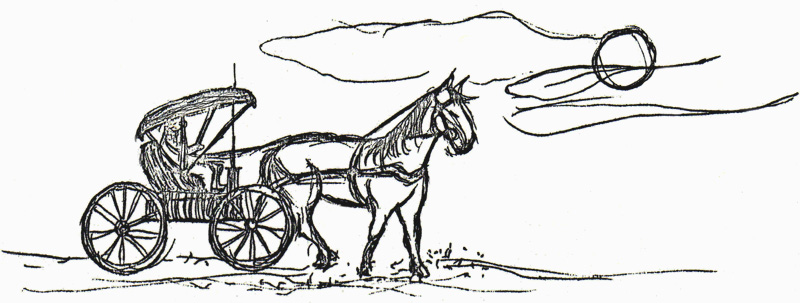

My mother was 23 when I was born and my father 35. They had been married four years. Shortly after they were married, Dad gave Mother a bicycle. Sometimes they would cycle 75 miles on a Sunday. Mother rode 12 miles downhill to Alpena once in 30 minutes when her sister was sick. Prior to my birth and probably because of the bicycle riding, my mother lost three boy babies all about three months before normal birth. With my impending arrival they gave up bicycling and bought a horse and buggy.

I liked my name until I was through high school. The third year that I taught school I lived with my Aunt Myra. She said, "Why don't you change the spelling of your name to Lorraine?" I did and when I went away to college the next fall it became official with me. The first time Arthur Mains went home with me he couldn't believe his ears when people called me Lorene. He kept looking around for another person.

The community into which I was born in 1901 was about 35 years old from the time the first settler invaded the wilderness of wolves, bears and lumbermen. It was located in Wilson Township. My uncle Frank who arrived June 27, 1868, was the first white child born in Alpena County outside the city limits of Alpena.

Our township had very distinct communities. There were the French settlements at Indian Reserve and around St. Rose's Church. There was the German settlement of Lutherans. The French Canadians were Catholic with names like Besaw, Rouleau, Chevalier, Prevo, and Sauve. The "Roosians", as they were called, lived at Wolf Creek. Each group spoke its own language and English with an accent. In addition there was a heterogeneous group of Protestants, largely Canadians. There was even an Indian Reserve at Hubbard Lake where a few Indian families lived. Some of these communities were three miles apart but might have been 500 as far as intermingling was concerned. My father, however, operated a blacksmith shop and worked for all groups within horse and buggy distance of six to ten miles.

In those days the only thing these diverse peoples had in common was voting and paying taxes. Each community did its own road work by which property owners could work off road taxes.

One of my uncles married a Catholic, one of my favorite aunts, but the uncle, it was said, "even talked like a Frenchman" and always voted Democrat! Sometimes I wondered what it would be like to have belonged to a "pure stock" community, for in my veins was the "blood" of various nationalities - German, Irish, Scottish, English and French which came to me via Canada, and previous to that, from Scotland and Germany.

When I was a very small girl my mother left me with my father when she went to town. She drove a horse, named Belle, hitched to a buggy. She bought groceries and also nails and iron and horseshoes for my father's blacksmith shop. He reshaped the iron shoes by heating them and nailed them on the horse's hooves. He twisted off the part of the nail that was too long and it fell on the floor. Sometimes he planed boards smooth and made bushels of wooden curls and shavings. When I got tired of playing around the shop I made a nest in the pile of shavings and went to sleep until my mother came home from town.

One day a man came to my father's shop with a mare and colt. The colt ran loose outside. I thought if my father could shoe a big horse I could shoe a small one. I tried to lift up its foot and it kicked me over. I wasn't hurt but dreadfully embarrassed because the men in the shop laughed.

I heard men say, "How much do I owe you?" My father would say, "Two dollars." Once I walked up to a man and said, "Give me two dollahs, please." Then my mother was embarrassed.

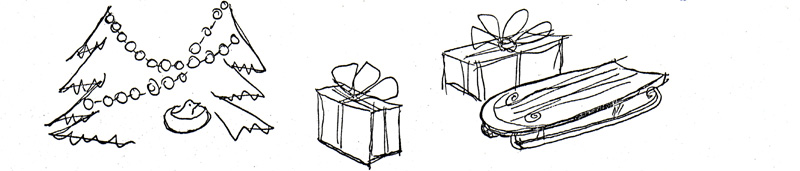

When I was two or at least three and I was the only child in the family, I got in bed with my parents one winter morning. They said, "Why don't you go out in the living room and see if Santa Clause came last night." I looked out and nothing different did I see. They said, "Go look again. Maybe in the dining room." There in the corner stood the loveliest Christmas tree I have ever seen. It was my first. It was looped with row on row of tiny candies of strings which I could bite off. But most delightful was a bird's nest with tiny candy eggs. It was low enough so I could peek into it. The tree was the gift that I remember. What fun to eat the candy off the strings and marvel at how a bird's nest could have candy eggs.

Perhaps it was the next Christmas when another exciting thing happened. I had been sick with tonsilitis and was lying on a couch in the living room near our big warm stove. I was dozing but my mother thought she heard a noise on the back porch. She stepped out to check and get some wood for the fire. She came in with a beautiful sled and other goodies. She said Santa Clause must have seen us through the window so left the things outside. I wondered and wondered how I could have missed hearing him deliver such a big package.

When I was two or three my father and mother gave me a little black short-haired dog named Jack. He never left my side. If I dropped asleep in the high grass he stood guard and notified my mother when she looked for me. If I climbed a fence and got caught on the barbed wire and hung, he barked until I was rescued. My mother made me pink and blue gingham dresses but when I became such a tomboy she made heavy dark denim, and I played in the shop and climbed trees and fences to my heart's content.

About two blocks from our house was a store. Every day my papa gave me a penny and Jack and I trudged to the store for candy. If there were stray horses or cattle, Jack would bark at them and scare them away. On the return, we would sit in a tiny hollow hidden from the world and share the candy. If Jack ever wandered from my side he sprang back as I whistled owl-like, "Whoo! Whoo! Whoo!"

When I was very young I wanted to hold a bird in my hand. When the sparrows flew into our yard for crumbs I tried to catch one. One day the men at the shop said, "If you put salt on a bird's tail you can catch it."

For days I trailed after birds with a salt shaker in one hand, tiptoeing up to catch a bird unawares. It was no use. I fell into puddles. I got caught on fence wire and fell off lumber piles. I finally gave up puzzled. Can you catch a bird by putting salt on its tail?

Some years later I had another sad experience. Across the road from the shop we discovered a bird's nest on the ground. Every day we went through the fence to note the progress. The eggs finally hatched. We watched the four baby birds grow. One day I got there just in time to see a snake start to swallow the fourth bird. There were three lumps in it. I screamed and danced up and down. My father thought I was being killed. He raced over and killed the snake. It was too late.

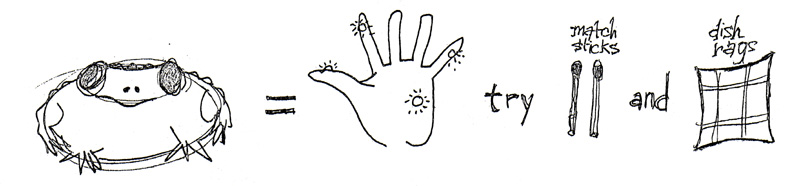

Getting rid of warts was a serious childhood problem. First most adults advised me to stop playing with toads. Nothing happened.

Hired girls seemed to be more imbued with wart lore than parents. Cures involved slyness and secrecy. Once I was told to steal my mother's "dish rag" and hide it so it would never be found. I still had wars. I thought perhaps the dog had dug it up.

I remember gratefully the hired girl's next suggestion. She told me to rub a match head on each wart and hide the matches so they would never be found. I hid them under the porch. Presto, when I next thought about the warts, they were gone!

One of the delights of my childhood was to go to Alpena with my father. Mother usually stayed home with the babies. I put on my good dress and my shoes and long black stockings. It was an all day trip to drive 12 miles with horse and buggy, shop and drive the long trip home.

Once my parents let me out to run on the board sidewalk. As we drove over Potter Hill we smelled the pungent odor of the tannery on the river bank where the Washington Park is now. There were long piles of bark piled like long sheds with peaked roofs. The bark was used in tanning hides. There were rafts of logs in the river in spring and summer, and there were mills on the shore along River Street. There were piles of fresh smelling sawdust.

My father bought iron and kegs of nails and shop supplies and flour. We ate at the Globe Hotel at noon and fed our horse some oats and hay in the yard at the back. On the trip home we had a lunch of crackers and cheese or bologna and crackers. We stopped at a spring by the road for a drink. Darkness settled down and I was asleep by the time we drove in at our gate.

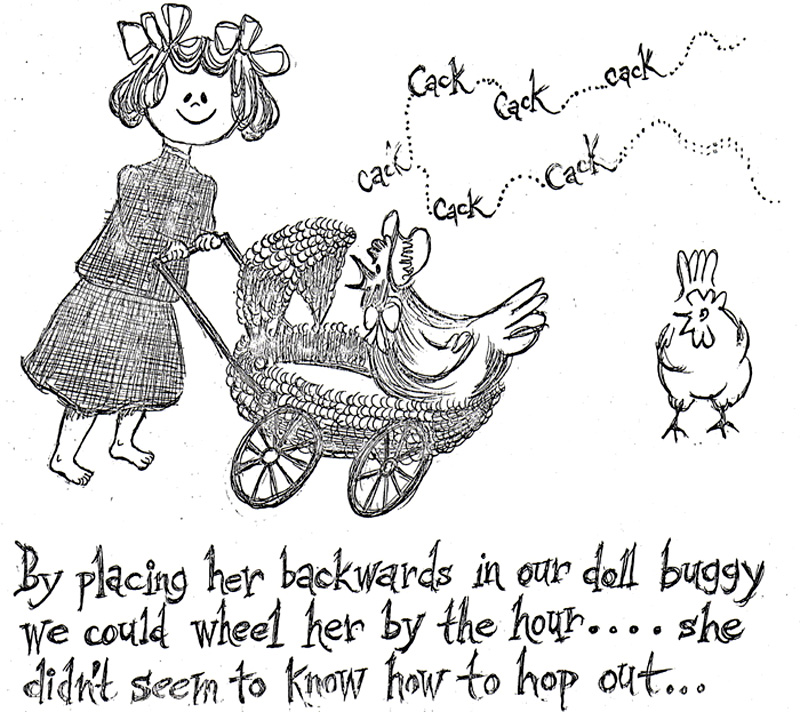

As a little girl I had two dolls - a rag doll that my mother made which I loved and took to bed, and a bisque doll that I lost in the high grass and left out all winter. My younger brothers and I always had a family of kittens which we dressed in doll clothes and wrapped in blankets. They did not appreciate our ministrations and pulled off the clothes and hid away when our backs were turned.

One year our luck changed. Stubby, the hen, became our constant, more or less willing companion. She had been a white hen until she evaded us many times in the coal bin in the blacksmith shop. We were not as white either after she was caught. She had lost some toes in an exceptionally cold spell and, poor thing, was blind in one eye. We could catch her on the blind side easily and by placing her backwards in our doll buggy we could wheel her by the hour. She didn't seem to know how to hop out. She wore bonnets and blankets and talked to us in a henlike manner, "Cack, cack, cack." She ate when we ate, sharing large slices of bread and butter and jelly. She was a most satisfying, manageable companion.

One day nature took its course and remembered she was a hen and not a person. She tried to lay too large an egg and ruptured the egg sac. She died and we buried her with great sadness and weeping. We had lost a dear playmate. We dug up her burial spot several times in curiosity and grief.

When my oldest brother and I were small, my aunt Ida gave my mother a hand occasionally on extra housework. But when the third and fourth babies arrived, we had a series of hired girls.

Eva was a loud voiced, red cheeked French girl, very jolly and good at putting us to bed. We loved her accent and her big voice as she rocked my baby brother, Oran, to sleep. She spent a half hour each night saying her prayers in a manner new to me with rosary and strange signs.

A few weeks after she had taken over our household she was called home. Her favorite young brother had died. She returned to us in mourning, wearing black dresses, black aprons, black petticoat and black underwear. Instead of singing the baby to sleep in her usual raucous tone, she rocked him saying in a sing-song voice, "Ahh a ahh a ahh a." We never forgot her grief.

One summer a large raw-boned Irish girl worked for us. She had a happy careless attitude toward work. catch as catch can between stories and songs. She spent each summer evening in a gathering of the young folks in the neighborhood. Frequently she came singing down the road at midnight. She took off her clothes as she came in the house and left them as they fell on the way upstairs. She was usually late for breakfast and ate on the run. She would skim the cream from a pan of milk, spread it on a large slice of bread, sprinkle some brown sugar on it and soon be ready for the day's work. The O'Tooles were large hearted neighbors and so my mother tolerated a little inconvenience.

Another time a girl with a baby and no husband worked for us. That made two babies in the house with my new brother, Bobbie. A positive welter of diapers ensued. I was seven and rocked babies indiscriminately. The hired girl sold me on the idea that to rinse soiled diapers would make my hands white. I advanced this idea to a visitor, Aunt Myra, who laughed merrily as I sudsed soiled smelly diapers. From that moment on I lost confidence in beauty aids!

I cannot remember learning to read. I can remember learning my letters. I sat on my mother's lap by a window in the corner of the kitchen waiting for my father to come to meals. In front of us on the cupboard worktable sat a square tea can with almost all the letters. Maybe it was ABC tea. At any rate I knew my letters when I went to school.

At first I did not have a book so did not read. As soon as I had a reader I stood beside the teacher and repeated the stories word for word without looking at the pages. Soon I had a second reader and a third grade book. To keep busy I wrote the day's story with the book closed. The teacher was suspicious and removed the book. The words came just the same. I do not know when I lost this ability but it was sometime between High School History and now.

I did not have the same acquaintance with numbers so repeated the third grade for arithmetic's sake. I thought nothing of it and read merrily along. I finally read all the books in the school library by the time I finished the eighth grade, including a set of Charles Dickens works.

When I was 5˝ my mother and the teacher decided I could go to school six weeks in the spring to get used to the idea. I was very shy so this was an initiation period. Long before this I had decided that I would be a teacher when I grew up. I was very anxious to go and eat my lunch from a lard pail like the other kids did.

On my first day I timidly loitered on my mile walk to school. On arriving, classes had begun so I rapped on the door. The teacher looked at me curiously, asked my name and then remembered the bargain with my mother. She took me to the very front of the room, past the big seats and big girls and boys to the smallest double desk. I sat with a beautiful little girl named Mary. During the morning I almost choked stifling a cough. Noon came. I would not leave my seat. Mary brought my dinner pail. I did not eat. The six weeks went by. I must have finally eaten. I did not leave my seat.

One day the teacher asked me to draw a rooster. I knew I could not perfectly reproduce one so I just shook my head and did not draw.

The next year when I was 6 I started to read and progress began. The big girls fussed over the little girls. Mary became my best friend. I went home from school with her one night. We played in the creek near her house and painted all the stones with blue clay. There were about 8 children in the family and the oldest sister helped us get ready for bed and heard our prayers. Later Mary came to my house and we got up so early we were at school before the teacher. We sat lined up on a stile at noon to eat our lunches. Lunches all smelled the same. We had hard boiled eggs and tomatoes or apples and bread and butter and cookies. Each morning I was eager to start. School became my life.

Driving through the country with horse and buggy the tin peddler came. Pots and pans were his offering and he would take money, old iron, or rags or food in pay.

Our house was a day's journey out from town and several times he begged my mother for a night's lodging, supper and breakfast in return for kettles and pans.

"The Jew man is here," we would say cautiously. He spoke in an odd wheedling dialect as he bargained. He had a long black beard and he wore a hat while he ate. He carried a huge buffalo robe and insisted on sleeping on the floor by the stove. I think my mother would have hesitated to offer him a bed. He looked so foreign and unclean.

Before she fried potatoes and eggs for him he questioned my mother carefully against the use of pork fat. It was against his religion. When she set food before him we peeked around the door to watch him invoke God's blessing by gazing directly up to the Heavens, then down, then on High.

It was and eerie experience having that old peddler sleep in our house. He rolled up in his robe in his ill fitting clothes.

When he left in the morning we children felt a mixture of relief and awe. My mother would smile as she remembered the pork fat that had greased the bread pan and tainted the holy one.

Another traveler through the neighborhood was the music teacher, Professor Lucas. My aunt Ida took lessons from him on the organ. He counted, "Vun und two und tree." He was a short, heavy set man who wore a tall hat. He beat time with a baton and rapped briskly on the fingers if the vun und two und tree did not come out right.

When I was five and Lee was three my mother took care of a little boy whose mother was dying with tuberculosis. She was being cared for by relatives who lived a block or so from us.

Each day mother sent me to get Arnold. I took his hand and led him home. He and my little brother, Lee, quarreled constantly over toys, especially a little red wagon. Because I was older and because he was a visitor I tried to stop the crying and fussing by giving Arnold whatever he wanted to play with. It was a constant struggle.

One day while I was taking his part he bit me. I said not a word but took him firmly by the hand and led him home. I reported the bite and said that he couldn't play with us again. My mother reluctantly but happily abided by my decision. He soon left the neighborhood and the incident was closed.

This may not be a memory. It may be a story my mother told. Our first horse, Belle, was so gentle I could walk around her, even under her. Once my mother found me whipping her in the stall. She did not step on me but cowered up into the manger. Mother heard the commotion and came to the barn and stopped it..

In spite of being so gentle she couldn't abide automobiles which chug-chugged speedily along, coming up behind a horse and buggy without warning in a swirl of dust. Belle reared and snorted and took to the ditch. She didn't ever upset the buggy, but came so close to it a dozen times that my father had to sell her and buy Old Fred who was unconcerned over cars or threshing machines or railroad trains, all of which gave Belle the jitters.

Another time I climbed a tree and ate sour apples. Soon I was doubled over in pain, My mother was busy getting dinner for men, but finally paid attention to me when she had it on the table. She called our old country doctor. He came with his horse and buggy three or four miles. He gave me some medicine and I went to sleep. He always carried pink peppermint candy and we were pleased to see him.

When I was small my mother was desperately frightened of thunderstorms. We children cowered in corners away from windows and chimneys. When my father came to the house he paid no attention to flashes of lightning or claps of thunder and we gradually got braver. He had a fatalistic attitude and said, "If it is going to strike it will. You can't stop it. Pay no attention."

Once he was driving home in a storm. Lightning flashed about him and the horse was struck. It staggered toward the ditch. Dad got out and led it and it kept slowly on. A few weeks later it died. Someone skinned it. It had a red streak in its flesh from head to tail.

My first experience with death occurred when a sixteen year old neighbor boy died. When I woke in the morning my mother was gone and Papa and I had to get breakfast. She had gone in the night just before he died. "His body was covered with brown spots," they said. For a while afterwards I examined myself each night for brown spots.

When the weather was warm about 12 or 15 of us walked home from school together, the big boys ahead, the big girls next and the rest of us bringing up the rear. Once we all gathered around a snake which raised itself about a foot off its tail and puffed its head at us. It was a puff adder, harmless, trying to frighten us off. The big boys killed it.

I had heard my mother tell about going to the Briar Hills to pick blackberries. Her mother kept a sharp ear out for a rattlesnake's rattle and occasionally heard one and shepherded her family to safety. I had also heard the story of a raspberry picking trip when they heard a bear on the other side of the clump of bushes and left in a hurry.

Sometimes my mother went to town for supplies for the store and shop. I was left to take care of my brothers. Before I was six I cared for Oran. Of course, my father wasn't far away. The first day was a long one. I set the baby on a blanket in the yard and tried to keep him from eating dirt. I fed him graham crackers and milk.

My mother kept store for about three years. Our house had two front doors. We used the one that opened into the living room. The other opened into a long hall to the kitchen. Off it were two rooms and a stairway. The rooms had various uses. The front room was large so that was the store. Mother kept, among other things, barrels of crackers, tea, matches, flour, prunes in boxes, kerosene and a lovely candy case. We children would slip in and take candy and crackers. That may have been the reason she quit the venture.

For several years the other room off the long hall was my father's office. He was the township clerk and justice of the peace and sometimes was a member of the school board. It was a bedroom when we had whooping cough and measles at the same time and kept the shades pulled so we wouldn't be blind.

Everyone who had work done at the shop stopped in at the store. My mother was a friendly soul and visited with all comers. I heard her say that she made enough to pay for the family groceries which we took from the shelves. I think she quit the store because we children "were ruining our teeth on candy" and because she was off on another venture.

I don't know why I was so terribly frightened of the dark. I was scared even going from one room to another. Of course, we couldn't switch on an electric light. We carried a lamp or lantern when we got old enough to be careful of fire. Mother left doors open so we could see the flicker of the lamp. It was dangerous to leave a lamp lighted in a bedroom with small children. We always ran the last few steps into the house after dark. It seemed SOMETHING might be behind us. I was quite old before I got over this feeling.

I suppose I knew that life was filled with dangers. Horses ran away or kicked people. I knew the story of how my grandmother was thrown from a sleigh and hit a stump. She was almost scalped and had lockjaw all one summer. She had to be fed liquids by forcing a little spout into her mouth.

I knew the story of the boy who was crossing the "plains” five miles east of us toward Alpena from one lumbering camp to a neighboring camp. A blinding snowstorm came up and he was never seen again. The next spring his bones were found inside a large rotted log where he had evidently tried to escape the storm and where he froze to death. That story filled me with dread.

One of the French neighbors went to town with a team and sleigh. He usually bought a bottle of whiskey and would be drunk by the time the horses took him home. One night the road drifted and the sleigh hit some posts at the approach to the South Branch bridge. "Poly," as all Napoleans were nicknamed, was found dead with a broken neck over the embankment. The horses went home alone.

When a neighbor died, people did not leave the family alone in the house with the dead body. They held "wakes." Everyone stayed up and drank coffee and ate bounteous food and visited. Sometimes there was a nip from the bottle. If it was a Catholic wake there would be candles burning at the coffin and periods of saying the rosary. The stories that came back from these "wakes" were weird. Some there were who could foretell a death by the howling of dogs or unexplained raps on the windows or doors.

We lived near a bog and there were those who had seen on a summer night a dancing light capering about the moor. A will-of-the-wisp was a nether world omen.

I suppose these stories contributed to the scary feeling my brothers and I had about the "Dark". Children experienced life and death and dangers and fear.

Our favorite play spot was my father's shop. We learned to be careful around machinery. When papa picked up the hind foot of a great big horse we stood our distance. Sometimes a horse would jump and pound around. My dad would take a flat rasp, if that was what he had in his hand, and trounce the horse on the hip. If that didn't work I have seen him put a twist of rope on its lips and have the owner hold it. Sometimes they would even put a sling on the back leg if the horse was especially obstreperous. A mean horse would lean on Dad who was actually almost under its belly.

It was dangerous work. When my father was 15 he had his knee cap splintered when a horse fell on him. It was a year and a half healing and ever after one leg was stiff at the knee.

My father smoothed the horse's hoof with a rasp. Then he tried on an iron shoe. He made the shoe fit by heating and pounding it into the right shape. He would fit it hot and the hoof would burn and smell. Then he cooled it and drove nails through the shoe which had been punched with holes. The nails went into the part of the hoof that had no feeling. He clinched the nail and twisted off the sharp pointed end. After the men and horses left, my brothers and I drove the sharp ends into the shop floor. We would pull ourselves to the roof of the shop on the pulley used to sling up the horse's leg. I could climb up a rope 20 feet and slide down. The shop had a flat roof and a leanto. We'd climb the leanto and run on the roof at times.

Sometimes my father would set wagon tires in the evening after supper. First he built a fire outdoors in a circle around the tire. He had a special hollowed out spot in the ditch. He brought tubs of water and filled the hole in the ditch. When the tire was red hot two men with tongs lifted it and whirled it in the water. This would cool the tire and shrink it to fit the wheel. Then they pounded it into place on the wheel. The water in the ditch bubbled and boiled from the hot tire. One night my brother, Lee, and I were leaping across, just dipping one toe quickly in the hot water. My brother slipped and fell in. My mother stripped off his clothes and put him in the tub of cold water and he was scarcely burned. I was shocked to see her strip off his clothes. I hit her.

When I was older I helped my father, holding boards as he pushed them through a planer. One day he pushed a board through, a knot fell out of the board and his middle finger dropped into the hole and was cut off at the first joint. He stopped the engine and held his hand and went quickly to the house. He told my mother how to stop the bleeding. Someone drove him three miles to the doctor. The doctor gave him chloroform to smell and sewed up the stump. I heard my mother say that my father sang a Gaelic song while the anesthetic was wearing off. He could never recall a word of that song.

In 1908 when I was seven, there were terrible forest fires all over northern Michigan. Smoke hung in the air all during September as we went to school. I wore an apron over my dress and covered my face with my apron as we walked home from school. We heard terrible stories of Oscoda and Metz burning. Railroad tracks burned as people tried to escape by train. People buried their treasures and, if possible, took their livestock to the edge of lakes. Soon barrels of clothing came from "down below" as southern Michigan was called. Some were sent to our community and were left in my mother's store for everyone to help themselves.

Our community seemed to be escaping. Everything was tinder dry. People said fire spread through the air. Then one night the 100 acre bog caught fire. It smoldered and burned and the trees at the edge flashed in flame. There was a westerly wind and it was blowing toward our buildings. The blaze raced with it.

Our barn was on the edge of the bog. We owned only an acre. Sparks flew onto the house and shop. My mother was expecting my brother, Bob, who was born October 21, 1908. She hitched the horse and tied him at the road and the three of us children slept on the couch. We were ready to leave at a moment's notice. All the men in the neighborhood spent the night fighting fire. Some pumped water all night long. Our well luckily didn't go dry. They ran home for pails and tubs. They took turns climbing on roofs of house, barn, and shop putting out sparks. When morning came the fire had burned itself out and we were safe.

We had an old long-bearded Irish neighbor, Tom Graham, who had fallen out with my father when he boarded at his house before Dad was married. No one knew why. His was the next house to ours, a 20 acre field away, and we children were warned not to play on his property. I remember his high pitched voice and how he prefaced each statement with "Min' ye!" He had come from the north of Ireland, was an ardent Orangeman who hated Catholics and flaunted his orange kerchief on St. Patrick's Day.

Tom Graham came to the fire and pumped unceasingly. The silence was broken in the night of terror. Soon he came to the shop and mother returned the call as soon as she took time out to give birth to the fourth child. When he and his wife grew old, my mother took them offerings of food and occasionally a bottle of homemade dandelion wine for heart stimulant.

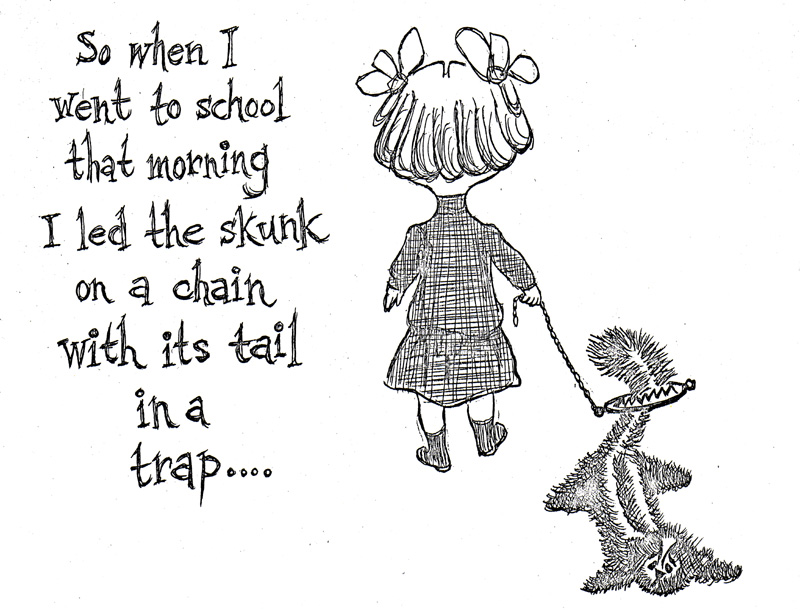

One time a skunk made his home under out barn. My father caught it in a trap. It was barely caught by the tail and he didn't want to kill it for feat it would smell worse than skunks usually smell. He said that as long as it was in the trap it would not spray its perfume. So when I went to school that morning I led the skunk on a chain with its tail in the trap. I stopped and gave it to an old trapper, Uncle Sol. That evening I stopped for the trap and ten cents.

Uncle Sol and Aunt Sally King were neighborhood characters. They were a wee wizened pair. They were English and had a way of leaving off h's from their words. They both smoked clay pipes. Their old log house reeked of smoke. The walls were brown, the rafters brown, the wide pine board floor was brown. The two old people had brown wrinkled faces.

Aunt Sally wore many layers of woolen skirts and a shawl. She kept pencils and paper and penny candy for sale for the school pupils. If she had to make change she turned her back, raised two or three skirts and in an inner pocket found a pouch of pennies. Uncle Sol was a trapper and skins were stretched and hung in his old shed. Dried herbs, dried apples and corn hung from the rafters.

We were very respectful in a scared way when we stopped to make a purchase. We thought of them as ancients. Their faces were like dried prunes and their eyes sharp slits. Uncle Sol's hair covered his neck. Her gray wisps were wound in a tiny bun on her neck. She had a son whom my mother said was "light fingered." My mother took them cream and vegetables. Otherwise I wonder how they lived and what became of them.

Miss "Woe-Betide-You" |

|

When I was in the third grade we had a large pompous teacher who threatened us on every occasion with wrath if we did not perform correctly. She ended every threat with "Woe betide you!" We called her Old Woe-Betide-You but we all quaked in our boots at her warning. The big boys and girls thought up dastardly tricks to pull but never dared carry them through. She boarded close to the school and for a time in the fall went home to eat her lunch. As she left she spoke her woe-betide-you piece "if everything is not in order when I return." Some brave souls decided that we should ring the bell just as she was coming. Everyone's hands were on the bell rope so no one could be blamed. The word came "Pull." The bell rang but every hand had left the rope except mine and Maggie McKay's. In came the enraged teacher looking all of six feet high. "Who rang the bell?" she roared. A few timid hands pointed to Maggie and me. I started to cry and shake my head, too scared to speak. I pointed a finger at Maggie. Poor Maggie was the only one to get ten cracks on each hand with a ruler. For years I was ashamed that I was a coward, and when she died a few years later I still suffered with guilt.

|

My brothers and I loved summers. We went barefooted as soon as the weather let us. School was out by the middle of May and we were free. We played in the barn, in the bog and in a pine grove back of the shop and, of course, in the shop. I liked to hide in little hollows and pretend it was a world of my own. Sometimes I ran around the corner and sat in a huge burned out pine stump. Violets grew on the ground in the shell of the stump.

When I was nine and a half and my brothers Lee, Oran and Bob were seven, four and two, my mother bought 40 acres of land one and one half miles away from the shop. Her mother had given her a pet sheep several years before, and she put it out to double and kept putting sheep out to double until she and the farmer each had 30 sheep. She sold hers for $12 apiece and with the $360 paid for half of the piece of land.

Every day was a picnic. Mother soon had a large garden and two or three cows. Every morning we drove to the "Fingleton" place, milked the cows and hoed the garden. Or rather, mother did. She had a green thumb and seemed pleased with more space for vegetables and children. She planted unusual vegetables like salsify, and flowers and peanuts in warm sandy soil. We could hardly wait for them to grow. In the fall we pulled the peanut plants and all along the roots the peanuts grew in shells, of course. They didn't get very ripe but we were excited to find how peanuts grew.

At noon we ate our lunch in a musty old house. We drew water from an open well with a rope windlass and a bucket. We didn't drink the water because a sheep had fallen into the well. The house was supposed to be jinxed because Mr. Fingleton had been killed several years previously by lightning coming down the chimney. The story was that lightning might strike again in the same place.

We camped out joyously for two or three summers. Mother milked the cows and at evening we returned home with cans of milk and vegetables. Then my father sold his shop and we moved to the farm. He built another shop at the new location and began working at the Shale Bed as a machinist. We were now only a quarter of a mile from the King School instead of a mile. I usually ran to school as I was getting big enough to wash dishes in the morning, and had only a few minutes to spare before the bell rang.

After my grandmother's last daughter was married, Grandma took a teenage girl to raise. The girl's parents had died of consumption so Clara Erick and a brother came to our community. Clara helped Grandma Clark with the chores and housework. People said she was a "simple" girl. At least, she couldn't talk plainly.

When Grandma went to town with the horses and democrat wagon or horses and sleigh to sell 30 lbs. of butter, as many dozens of eggs and jars of sweet cream to her customers, I walked over to stay with Clara. I was five or six and she was about 14. Grandma said I was "company" for her, but I have wondered since if I was not a chaperone for Clara and the hired man.

I helped feed the chickens and gather eggs. Sometimes the hens hid their nests in the hay barn. If we heard a cackle we ran to see where the hen was and could usually find the eggs.

I helped Clara make the beds. The mattresses were filled with straw so we swept up any that spilled out of the ticks. Once Clara wanted to play baby with me and put me to bed. I was deeply incensed and walked away. I didn't tell my mother.

Clara stayed with Grandma Clark until she was 18, and I imagine learned to do many things about the house as my grandmother was a stern taskmaster. When she was 18 she was free to go "for herself." She did housework for my Aunt Ida, and met a hired man who courted her. She was soon married with Grandma's blessing before "she got into trouble." She went to live in the Briar Hills, probably ten miles away. Mother and Grandma and I drove over to visit her with team and sleigh when her third baby was born. We had heard that she was feeling very poorly. She didn't live long after that. She, as her mother before her, died of galloping consumption.

Indians must have traveled over our farm because my father plowed up two skinning knives. In our uncultivated pasture land there was woodland and one bare hill that we thought had been a lumber camp site of an Indian camping ground.

![]()

Nearby was a swale that would dry up in summer. It had sticky blue clay that we fashioned into pots and dishes and dried in the sun. We wondered if the Indians had ever used our clay factory.

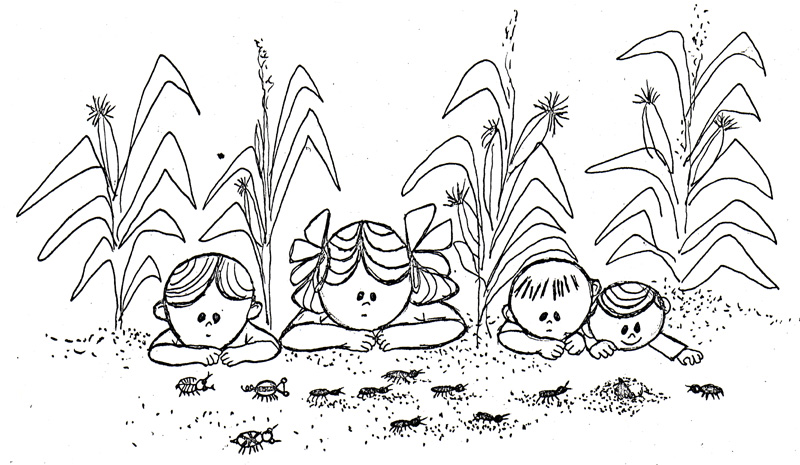

In the spring after the snow melted, we had a pond crisscrossed by logs and full of spring peepers. We always hunted for frog's eggs and usually took a jar of pond water and eggs to school to set on the windowsill and to watch hatch. Once we found frogs fastened together in pairs. We couldn't pry them apart. My father just said "Hmm!" when we asked the reason. We thought it had something to do with frog's eggs. Teetering across the pond on rotten logs usually involved wet feet and then we'd splash each other a bit for good measure.

In the summer the cows would be turned into the pasture. Usually they came to the barn at milking time but sometimes my brothers and I would go to the woodlot after them. If we left the open spaces a whirr of wings would scare us as partridges zoomed out of sight. We always thought about the Indians that stood in our steps to hunt wild animals a century or more before we walked the same paths to hunt cows.

Country roads were very seasonal in 1908. In the long hot dusty summer it was fun to plunk along barefoot in ankle deep silt, cut even deeper by wagon and buggy wheels. It was soft and warm as it squeezed between my toes, and I was never aware of dust which settled in a film on our furniture when the doors were open.

Most exciting were the winters. No one ever heard of snow fences and the drifts piled ten or twelve feet high in front of our house. My father cut foot square chunks of snow as he carved out a narrow road past our door for the mailman. He tossed the blocks sky high. Opening the roads in those days meant shoveling snow by hand and back. My dad made us children skis to skim over the tops of the fences. At school the boys made forts with alley ways, secret hideaways and turrets filled with bullet snow balls. They had snow battles at recesses and lunch hour.

Spring break-up was the most disastrous time for school children. One day I broke through thin ice and got wet to the knee. I ran to school and took off my shoe and long black woolen stocking and dried them by the school stove. I put my icy foot in cold water to cure the chilblains. It took a long time to dry my long underwear as I held my leg to the fire. I studied by the stove all morning and felt quite privileged.

As the ice melted and covered the roads with water, we executed a special feat. One farmer had a half mile fence of logs piled three high similar to a rail fence. Some of the logs were over a foot through at the butt. It was fun to balance along the big ones but tricky where the log's diameter narrowed. Sometimes falling off was a real splash but teetering along a log fence was one of the adventures of my childhood. My mother wanted me to wear boots but I wouldn't. I said they were for boys!

One summer when I was about ten or eleven, my brothers and I decided to edit a newspaper. We rounded up a notebook and pencils not too easily, and hied ourselves to the hayloft in the barn. A large window in the peak of the roof furnished a viewpoint and a ledge on which to write. We could get down either by pulley out the window or jump down inside from a high beam into soft hay.

We labored all one long delightful afternoon. Thinking back fifty years it seems one article was "Boy Loses Tooth in Dangerous Bareback Ride." The horse stumbled going down hill. My brother, Oran, went off over its head and a horse's hoof grazed his face knocking out a tooth. The tooth went through his lip, and mother had a shock and a dentist's bill to pay for a peg tooth. This occurred as we were riding three horses bareback from the road to the pasture. Another time Lee and I were racing. We stopped at the pasture bars. Lee stepped off the horse onto the end of a pole. It swung up and hit me smack in the head. I rolled off my horse to the ground, but after a dazed moment got up and gave chase and left the horse standing. Lee was younger than I and I could wrestle him. Oran could get the better of Bob. For a long time Oran and I teamed up in fights, usually besting the other two. This lasted a few years and then one day I discovered that all three brothers were bigger and stronger than I.. Then they held my hands behind my back and laughed if I took a swipe at them. They kept showing off how strong they were. I learned to treat them with more respect.

Another article was entitled "The End of the Express Wagon." That story told of hitching a calf to a little red wagon. All four of us held the calf until she was properly harnessed. We eased our hold and she leaped away, prancing and kicking up hill and down, over stone piles and through pasture bars. We ran over 20 acres to pick up the pieces. With great faith in his father, Lee said, "Dad can fix it."

And there was the story, "Tabby Leaps in Second Story Window to Have Kittens." Tabby clawed her way up the side of the house to an open window. She then selected my bed as the proper place to give birth to four kittens in the dead of night. My mother was not pleased but I was very excited. I related the story of the wet kittens arriving one at a time and now Tabby licked them. Her purring sounded like a little buzz saw.

The newspaper was well received by the family and the flow of exciting events continued. The next issue featured "Brave Woman Followed by Lynx."

One early evening my mother walked to a neighbor's house through a mile of quite heavy woodland. She took our small dog, Bouncer, for protection and carried a lantern. The road was not traveled in summer as it was narrow and partly corduroy; that is, logs laid side by side across wet swampy places. It was a good winter lumber road. Actually, there was a good road four or five miles around but my mother took the shortcut.

She went to engage a man to help in haying the next day and when her errand was completed she lighted the lantern and started home. Upon entering the dense woods the dog tried to walk between her feet and, almost immediately, an animal leaped along the road a few feet away but always beyond the range of the lantern. It accompanied them in great leaps, nervewrackingly close. Mother thought it was a bobcat or lynx and was just curious, but the dog took no chances. When she finally reached the clearing the noise stopped but Bouncer stayed so close she could hardly step. We decided our mother was a brave woman.

That was the end of the newspaper business. We were much too busy having adventures to write about them.

Some of the first sounds I remember were the lovely lilting melodies that my father whistled. He whistled in the shop as he hammered on wood or iron. When I was seven or eight I set myself to learn to whistle too. Grandma said, "Whistling girls and crowing hens always come to some bad end." The hens, of course, lost their heads. For weeks on end I puckered and blew and thought a tune. I finally learned to make a few sounds but never became much of a whistler.

Before my father cut off his finger in the planing mill, he played the fiddle for us children. Mother chorded with him and also taught us a few hymns.

At school we sang from a book called the "Knapsack." It had words but no notes.

When we were very young my father came home from town very pleased with himself. He had bought a gramaphone with a large horn and cylinder records. We played "The Preacher and the Bear" and "Pretty Redwing" over and over.

After I taught school I bought a phonograph and my brothers and I bought popular records and learned to dance. Oran became a vocal soloist when he was about 16 at the local square dances in the town hall.

School was always a delight to me, after the first few weeks. I never knew when I learned to read. By the time I was in the Second Reader I could read a story once or twice and repeat it word for word. I could close my book and write it exactly.

I was not so good in arithmetic. I had to repeat the third grade. And when I met up with fractions in the fourth grade I was hopeless. I cried in class.

My teacher invited me to spend the night with her. She expected me to take my arithmetic book but in the excitement I forgot it. So that night I cut my first paper dolls out of The Ladies Home Journal instead of studying. I felt very shy when I had to sleep with my teacher. The next morning we had a strange thing for breakfast - toasted shredded wheat eaten with butter. My mother said she was a food faddist. For some strange reason I never had any trouble with fractions after that.

I had the same teacher from the 4th through the 8th grades. I thought she was wonderful and perfect in every detail. Not many pupils attended High School in those days, but she urged my mother to send me to High School. She started promoting it when I was in the 7th grade. My teacher was a widow. She had a son my age named Alex. I had a secret fondness for him for several years. I giggled at his jokes.

Once I stayed after school to help wash blackboards. I walked home with the teacher. There was a glacial boulder in our path that the kids would leap upon and jump from. She said, "If that stone could only tell us of its travels!" I had never thought of stones as anything except something troublesome to farmers. The idea struck me and I never forgot it.

After I was in the fifth grade we lived on the little farm near the King School. My teacher set up a point system for which all the pupils kept charts. We kept track of brushing teeth, washing before meals and having our own drinking cup instead of the school dipper. The cup was called a folding cup. It was in sections and folded down to an inch high. It had a cover. She promoted a water cooler instead of a water pail. We got points for all kind of chores such as doing dishes, making beds, sweeping and farm chores for the boys like carrying in wood and cleaning the barn. We turned in our charts for gold stars.

In a country school we could observe exactly how each class was taught. In the fourth grade we could listen to the subject matter and study geography from a large map with the eighth grade. Each grade went to the front of the room and sat on a long bench called the recitation seat. Once in a while as I got older the teacher let me help smaller children with their reading or spelling lessons.

When I finally started to teach school the day I was 18, I felt very capable and tried to do exactly as I had seen Mrs. McLennan teach the five years I had been under her tutelage. I had six weeks training beyond High School.

The last day of school in May was a joyous one. We had a school picnic. One year 36 of us got on the train at the Shale Bed. The station was called Paxton. The teacher paid our fares and we rode seven miles to Lachine. We arrived at 11:00 o'clock. We walked to Manning Hill and had our dinner and roamed the hill for wild flowers. Then we went back to Lachine to a roller skating rink and tried for the first time to skate. We took the 4:00 o'clock train home and completed for many of us, our first train ride.

However, it was not my first train ride. When the Shale Bed opened about 1908 there was an excursion on the new railroad line to Alpena. My father took my brother, Lee, and me. Everything was free. We were met at the depot by a livery rig. We had a free dinner. In the afternoon I went to my first movie show. It was scary. Trains came right at the audience and men on horseback galloped over our heads. I spent my time ducking. It was a wonderful day.

When I finished the 7th grade I had to go to the Alpena Court House to take an examination on two subjects. When we were in the 8th grade we had to pass in eight subjects. If we passed we had graduation exercises in Alpena with all the county graduates. Seventh graders usually wrote on all the subjects for practice. My mother arranged for me to go to town with a girl friend whose father owned the first car in our community. I wore a blue serge middy blouse trimmed in white braid and a pleated blue serge skirt. I walked out to the road by the schoolhouse to be picked up. The car had a canvas top but it was folded down. I had my first automobile rode and was surprised how quickly we got to town.

The next year in 1915 I passed the eighth grade and went to live in Alpena with a cousin. I began a new life in High School.

The summer I was almost 15 I came home from High School to the farm slightly changed by my introduction to Algebra and Ancient History. I had one girl friend in Alpena but I was still so shy that no boy had ever spoken to me. I spent a rather morose summer. My brothers, Lee aged 13, Oran aged 10, and Bob aged 8, and I were in charge of cultivating potatoes and corn, and cutting and hauling hay on our small farm. I wore overalls like the boys did. That was not done by girls in 1916. I wore my long hair stuffed up under a cap and announced that I was to be called Tom. The boys agreed but my mother didn't go for it. I milked cows and rode horses and a boy's bicycle but did not stir far from home.

My father worked away from home at the Shale Bed so my mother supervised our farming when we were in sight, but out of sight we were carefree and careless. We wandered off from our farm chores and left the horses standing at the end of corn rows. When we worked we used two cultivators with Lee and "Tom" on the handlebars and Oran and Bob on the horses' backs guiding. We took off 20 acres of hay and got it into the barn but were not always too successful with our loads. Sometimes a load would slide off halfway to the barn and we would have to fork it back on the wagon.

Neighbors who came to the farm or shop thought I was one of the boys. I didn't take off my cap. On Sundays I wouldn't go to church. I sat in a smooth spot in a huge lilac bush and read. I didn't know why I acted so oddly but I suppose it had something to do with leaving child hood and growing up.

Suddenly toward the end of the unexciting, boring summer of 1916 something wonderful happened. My father bought a secondhand Overland car. The salesman drove it out from Alpena. My father had a stiff leg so did not think he could drive a car. My brother Lee, not quite 13, got the first and only driving lesson. We drove a mile and back and the salesman left. I was outraged to think that I didn't get the lesson as I was almost 15!

We spent the next weeks driving the car in and out and through the barn. Soon Lee and I took turns taking my father to work and going after him. It's a wonder we weren't all killed. I turned corners too fast and just missed a farmer's front yard and house once. Twice I landed in a ditch right side up and the men from the Shale Bed got me back on the road. I was highly embarrassed and learned to turn corners more slowly.

It was a great sacrifice for me to leave the car and go back to High School that fall. I did not get home again until Christmas, and then the boys had scarlet fever and I stood outside and talked through the window. I spent the holiday with a cousin's family and had dinner at Aunt Annie King's home. The car was forgotten for the time being.

My grandmother was dependable. She was a part of my life until she died when I was 17. She lived one half mile from us and I often stopped at her house on my way home from school. When I was small my mother left me at Grandma's when something unusual happened like a trip to town or a funeral or a new baby. I was about three or four when she taught me a song as we hoed the garden. She did everything vigorously so the weeds and dirt flew as we sang over and over,

"Let a little sunshine in;

Let a little sunshine in;

Open wide the windows, open wide the door,

Let a little sunshine in."

She believed that morning hours were golden, noon were silver, and evening were lead. She got up at 5:30 and had breakfast as soon as chores were done so the hired men could get to work at 7:00. Early in the forenoon her kitchen smelled of bread or cookies or pies. She served meals promptly at 15 minutes before noon and at 5:30 before evening chores.

For years the whole family of aunts, uncles and cousins celebrated her birthday on June 11th. Once there were 60 of us. Once all the horses and rigs met at our house and we all went in procession up her lane. I think she was surprised that time, but then she always acted surprised. What delicious food the aunts would bring. I had six boy cousins my age and only one girl cousin. We played hide and seek until dark. There were 34 cousins altogether, some older, some younger. There was a long table in the kitchen and the table in the living room would be stretched to its limit. The grownups ate first. The tables were reset and finally all the children had eaten their fill. Then we all squeezed into the parlor, and Aunt Ida or Aunt Myra played the organ. We sang hymns and always ended with "God Be With You Till We Meet Again." That was the signal to gather up the dishes and go home.

The grownups seemed to have a good time. There was laughing and banter. One uncle always held me on his lap and asked for a kiss. One year my father and brothers did not attend the party. Mother and I walked over and it was almost daylight when we started home. I had never been out so late.

My youngest uncle was married when I was very small. He and his family lived with Grandma. I helped take care of Uncle Elmer's three children, Ivan, Arthur, and Inez. I was never given any money, but one winter my aunt made me a red woolen dress. About the time the children were all in school my uncle died. His wife stayed at Grandma's for a time, but in a year or so she and the children left and she remarried. By this time my grandmother was 76 years old and not well. She had managed the farm for almost 30 years. My uncles persuaded her to sell to my mother and father, and grandma lived with us for a few months until she died just before she was 77.

When I was 12, my mother went to Ann Arbor for an operation for goiter. She left me to keep house for my father, three brothers and my uncle Bob, a deaf mute. She left me with quantities of bread, cookies and cake, baked beans and canned fruit and meat. She finally did not have the operation until many years later because my father and grandmother, both of whom were suspicious of doctors, were nervous about the outcome. She stayed three weeks, however.

My brother, Bobbie, was only 5 at the time. I helped him write a letter to mother. He drew a picture of his dog, Bouncer. I thought he was adorable and smart as a whip. During the day while I was in school he went with my father who was cutting firewood for the neighbors with a gasoline engine and buzz saw. In the winter each family cut a huge pile of hardwood from their woodlot. After it was cut, it was the job of the children to pile the wood in long rows or put it into the woodshed.

While mother was away I felt very capable until I ran out of bread. I started in to mix bread boldly with a large amount of ingredients. I walked over and asked my grandmother for a few fine points and she came over and kneaded it. After that I felt at ease about bread making. I wrote to my mother and was annoyed when she didn't send me a cookie recipe.

One of Grandma's favorite sayings was "Waste not, want not." She thought it was a sin to waste food or any resource.

A few years later when I was 15 and home from high school for spring vacation, both my father and mother went to a Grange Convention in Battle Creek. I was left to keep house. A day or two after they left, I popped out in little blisters all over my body. I walked over to Grandma's but stayed out in the yard away from my young cousins. She said it was chickenpox and to go home and stay in bed as much as possible. We depended on her in a pinch.

Grandma was of medium height. She was a plump woman. She always wore a long gathered apron; white for "good" and colored for workdays. She parted her hair in the middle and combed it very smooth into a knot at the back. Her white hair waved a bit but she thought curls frivolous so smoothed them out. She had raised 10 children to adulthood and lost three as babies. She was widowed at 48. I expect she had rheumatism. She walked with a sort of rocking motion.

I was away at High School when she lived with our family but I came home at Christmas time. That was 1918 during the First World War and during a flu epidemic that took many lives.

A neighbor, Mrs. Orville Lancaster, died of the flu and my mother was caring for her. Mother brought her three year old daughter, Mary, home. I wept for the sadness of a little child's helplessness and lost days of living.

It was a sad holiday. Grandma was not well. She sat by the stove and rocked and drank tea from a little teapot. She told me a little of her early life as a child in Germany. She could not reconcile the hate for Germans, nor the fury of the war. I went back to school and did not see my grandmother alive again. She was buried on Easter Sunday in 1919 when I was 17. Easter seemed an omen of her release. We had another gathering of all the relatives but Grandma's birthday parties were over.

When I was a small girl my mother took us children to church and Sunday School. It was a lovely little white church that held about 100 people. Our Sunday School class met at the back, but with little effort we could hear what was going on in the adult or primary or other classes. I loved to go because my Uncle Fred was superintendent. He led the hymns in a loud voice. His wife, Aunt Myra, was my teacher for several years. Sometimes she stopped and picked me up. We read from our "Quarterlies," as the lesson material was called, and from the Bible. It seemed a strange ancient book. I looked forward to the little magazine, The Classmate. In the summer we walked in the cemetery before church and looked at the graves of our relatives.

At Christmas time there was always a program at night, and two large Christmas trees with candy for every child and sometimes other gifts. The men would build a high platform over the altar so everyone could see. The church would be filled with people shedding heavy clothes. One time my grandmother's horses and sleigh stopped for us. We all got in the sleigh box filled with straw and pulled heavy buffalo robes over us. It was below zero. The moon was bright and the snow glistened. It was so cold the horses' breath could be seen in frost. Their bells made a crisp, ringing sound. When we arrived the men put the horses in an open shed at the back of the church and covered them with robes.

Once my father gave me a pair of house slippers to sneak on the tree for my mother. She wondered why I had disappeared so quickly and was surprised when her name was called. After the program a great stamping and the clang of sleighbells would be heard at the back of the church. Someone would shout, "Santy Claus." Santa would run up the side aisle, hide behind the trees, give us one glimpse and then disappear. We could hardly stand the excitement. He did his work quickly and left. Sometimes we didn't even see him but we knew he had been there. The trees were beautiful and towered to the top of the church. We clutched our box of candy and snuggled into the cold sleigh as we rode home. The high moment of Christmas had been reached. Some of those years we didn't have a tree at home. Our gifts would be on a chair near the stove when we woke up.

One year when I was about nine my mother told me a secret and told me not to tell. She was combing my hair in braids and rolling them up with a big bow behind each ear. (She held the braid in her teeth and it was always wet when it was rolled up.) She said there was no Santa Claus. I went to school with a heavy heart but felt awfully responsible about not telling my brothers. I never knew when they found out.

As I grew older it was my delight to go to Sunday School to see my friends. There were several boys in my class. Sometimes I hitched up the horse and buggy and drove from the farm to church, about three miles. A young neighbor boy hitched a ride and people teased me about him. I liked the church ice cream socials when the mothers brought homemade ice cream and cake. We met at the parsonage while it was still light. Benches and tables were set up under the trees. For ten cents one could be filled and for twenty cents seated.

There were box socials too. The girls packed a lunch and decorated a shoe box. No one was supposed to know which girl brought which box. The boxes would be auctioned off. The boys would then eat lunch with the girl who had originally owned the box.

I was not quite 14 when I went to high school. It was the summer I was 16 that I started to go to socials. Once at a pie social two boys bid on my pie. The winner, or perhaps you might call him the loser, paid five dollars. It was raspberry pie and quite seedy and runny. I didn't think it was worth five dollars.

Our community had, and still has, two churches. Around the corner of the cemetery from the Methodist Church was the Free Methodist Church. The neighborhood was rather sharply divided. Methodists didn't drink, play cards or dance, unless they were wayward teenagers. Free Methodists observed the same restrictions but added a few others. They wore no jewelry, and the women and girls wore no flowers in their hats. No one wore makeup in those days, but the Methodist ladies curled their hair with a hot curling iron heated over a lamp.

Two of my uncles married Free Methodist brides so the families were divided. Dyed in the wool sectarians did not go back and forth to each other's churches, but some of us did.

Every summer for ten days the Free Methodists held a camp meeting in a maple grove near the churches. They set up a large tent with benches and sawdust for floor. The members and pastors addressed each other as "Brother" and "Sister." The preachers were leather lunged. We lived a mile and a half away and on a summer night could hear the exhorting and singing.

When people repented they gave long loud testimonies. Sometimes there was a great deal of weeping. Women fainted. Families would plead with an errant member. Someone might feel called to sing praises while the minister called down hell-fire on the damned. Kneeling people prayed loudly - especially for drunkards. All this was going on at the same time. It was exciting and hair raising.

My Aunt Barbara was one of the devout. She was greatly opposed to dancing. However, when she got the "power" she became joyful and, so my mother said, danced a schottische up the aisle. She wore a saintly expression.

Methodists held revival meetings in the church. They were never quite as unrestrained as our brethren around the corner. Once I was certain the minister was preaching directly at me. I was moved, but not enough to make a public statement. I joined a "student's church" in Ypsilanti when I was 21.

I don't remember very much about my mother when I was young except that it was delightful to get home from school and smell dinner cooking. When she was away the house was cold and lonely. I hated to go home when she was away.

Sometimes my brothers and I were very ambitious and helped with chores. Sometimes we all got scolded roundly for not carrying in wood and letting the fire go out. We burned wood in our cook stove and mealtime was late if the stove was cold.

My mother moved very fast. She could make a pie while the teakettle was boiling. If she spilled salt she threw a little over her left shoulder so she wouldn't have bad luck. She never started a new project on Friday. It wouldn't turn out right, she said. At the table Ma waited on everyone. She knew what my father wanted before he spoke.

She always looked over her left shoulder at a new moon and made a wish. She watched the changes of the moon very carefully, mostly for weather changes but also for planting time.

Until my mother was 80 she scrutinized the weather carefully each day. A mackerel sky foretold wind. Dad depended on mother's predictions at haying and harvesting time when it was important to get the crops dried and in the barn before a rain.

I was brought up on the following sayings:

Rain before seven, quit before eleven.

No dew, rain before two.

Rainbow at night, sailor's delight.

Rainbow in the morning, sailor take warning.

Evening red and morning gray sends a sailor on his way.

Evening gray and morning red makes a sailor shake his head.

In those days we were our own weather man and mostly it was Ma who knew when a blizzard was on the way. Then it was time to put water and feed in the chicken coop lest the coop was covered by drifts.

Ma loved the earth and growing things. She also loved to go barefooted but ran for her shoes if she saw a horse and buggy coming.

Once when I was about 12, I thought my mother was pretty. I saw her dressed up to go to a Grange Convention. She had a hat with a plume and a high necked dress.

My mother was an ardent reader, either magazines or library books from the State library. Books came to the Grange Hall. My father read the Alpena News very carefully for an hour or so. Mother skimmed it in ten minutes.

Ma tackled anything. She kept store for three years. Once she raised a flock of sheep by putting them out to double. When she sold them she made a down payment on our second home. She always ran the house. That is, she provided the larder either from canned fruit or vegetables, or fresh garden supplies. She was in charge of eggs and butter production. She sold them and bought staple groceries. Sometimes she had customers and sometimes she went from door to door and peddled. Once when I was 11 or 12, Mother raised quantities of flowers. We bunched them and took them to town. She persuaded me to stand on a street corner and try to sell them while she shopped. A lady came by. "Would you like some flowers?" I timidly asked. She shook her head. I left my post, went back to the buggy and that ended my selling career.

Once Ma went into the bee business. She had a dozen or so hives but started with one. She wore a net over her hat and overalls and gloves when a hive swarmed. Sometimes a group of young bees would leave the old hive and usually settle in a huge buzzing mass on a post or tree near at hand before setting off for a new home. We rang bells and pounded pans so they would settle, and then Ma tried to get them into a beehive before they took off for the woods to a bee tree. Where the queen went the bees went. Ma usually saved the swarm from leaving.

Once the bees lighted on Mother and crawled inside her net and almost stung her to death. Dad and a neighbor came to the rescue. They got the bees in the hive. Mother was almost unconscious. They put wet clay on her and she recovered. During the fracas we children kept a safe distance. I think Mother lost interest in bee keeping after that experience.

Once Mother raised geese to sell for holiday dinners. They nipped our kitten's tail, chased our dog and even chased us children. The day finally came when Mother decided to ready them for dinner tables. She tied ropes around their legs. Dad fastened them head down from a beam in the shed. Then he cut their throats so they would die. In the meantime, Mother started to pull off the valuable down feathers for pillows, stuffing them in sacks. It was a scene of flying feathers and dripping blood. All four of us children stood watching and crying and yelling, "Stop!" Poor Ma, under great stress, whacked us sent and us to the house.

The first time Ma visited her sister who moved to Flint in 1915, she arrived in the strange city late at night. She took a street car to Ash Street which she had discovered was only one block long. She borrowed some matches from the street car conductor, went up on porches until she found the number and aroused her sister at 1:00 AM to let her in. Ma didn't scare easily.

When she was 80 she flew in a four seater plane from Alpena to Detroit, took a taxi and arrived to surprise me in the same way.

When I was born in 1901, the only way to have seen my home community, Wilson, from the air would have been by a bird's eye or from a balloon. Balloons were used at the time of the Revolutionary War and earlier in Europe. When I was two years old the Wright Brothers made their first airplane flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. I made my first flight when Richard was two and I was 40 from the Soo to Detroit in 1941.

In 1963, however, I flew with Bill Russell over the three square miles area that saw nearly all of my comings and goings the first 13 years of my life. In the airplane we covered the area so fast I could see it all in a glance. I was 18 years old before I ever left the soil of Alpena County, Now I have flown to the other side of the earth.

I was 12 when I had my first automobile ride. What a different world received me than the world in which my grandchildren were born. I wonder what they will be doing differently in 50 years.

I wonder, too, what I was like so long ago. In my picture at two I wore a long dress and was a thin serious child with wide open eyes. My hair was wispy and light brown.

At eight I was tall and thin. I wore my hair parted in the middle, with two braids rolled up and tied by a bow of ribbon behind each ear. I had a shy smile.

At 12 I had long legs and was almost as tall as I am now. I could run very fast and loved to climb. I was thin and lanky.

At 15 I thought I was very ugly. I spent all my time studying and reading and working.

At 16 I thought I was quite pretty because a boy took me for a buggy ride.

Uncle Bob With One Arm was a part of our lives for many years. As a young man, he spent vacations from the Flint School For The Deaf with Mother and Dad. When we were growing up he lived with us four or five years, and after I left home he was with the family ten or more years.

He was 12 years younger than my father. As a baby he had scarlet fever and became deaf just as he was learning to talk. He was the youngest of a family of eight. His mother died when he was three. His father was 62 when he was born and died when he was a boy of 13.

The Cochrane family home was at Grand Cascapedia, Quebec, on the Bay of Chaleur. A few years after the mother died, when Bob was about seven, the family moved to Alpena, Michigan. The four older boys worked in the lumber business - in the camps in the winter, in saw mills in the summer.

Bob learned to make signs to make himself understood. He could make a few sounds, remnants of the baby talk he had learned before becoming deaf. He did errands for the two sisters who kept house. He carried hot lunches to the brothers at the mill. At noon the machinery shut down while the men ate. Bob played while the men ate, waiting to take the lunch pails home.

One noon, when he was 11, the young deaf boy was there when the whistle blew to start work. He, of course, did not hear it. The engines started; the wheels turned and Bob's right arm was caught and mangled in a machine so badly that it had to be amputated.

About the time he recovered the father died, the sisters and brothers married, and the home was broken up. Bob was sent to the School For The Deaf in Flint where he learned to read and write and learned the sign alphabet. He stayed at the school until he was 21. After he was 18 he worked as a janitor.

By the time my brothers and I had arrived, Uncle Bob had spent months with each of the six Cochrane families - doing chores in camps, helping in blacksmith shops, gardening and cutting firewood.

He was a big strong man with an enormous appetite. He was immensely proud of the fact that he could tie his shoe laces with one hand, plus the myriad of other activities that most people do with two hands. He showed some talent in art at the school and learned to decorate wooden bowls with burnt design as well as painting.

When I was about ten he came to live with us for five or six years. He was 33 when he came. Lee, Oran and my brother, Bob, teased Uncle Bob. He was most patient and usually played tricks on them. He could usually get the boys to help him clean barns. He and I were very good friends. He taught us how to spell and talk with our hands and carefully spelled slowly so we could understand him.

Once in a while he became very angry. Then he would get a paper and pencil and start out, "Hell, damn" and relay his problem. My Mother always laughed at his "Hell, damns" and tried to soothe his anger. Dad bossed him around like a little boy and gave him some very stern signs at times. Mother was peacemaker.

When the boys were in their teens Mother cooked for five "men," including Dad and Uncle Bob. By that time I was away at High School. To show the enormous appetites she coped with, one winter she baked eleven barrels of flour into bread and used sixty pounds of comb honey.

Money was very scarce in our family, but Dad bought Uncle Bob's clothes and his tobacco. He chewed fine cut from a pouch. I think he never had any money except gifts.

After a few years Uncle Bob went to the Soo and stayed with the Bill Cochrane family. The children there were good to him. They also learned the hand alphabet.

The next thing we knew about him, he was hiking over the northern part of the lower peninsula of Michigan with a heavy suitcase strapped over his shoulder, selling extracts and spices. On one of his visits he told us he had a girl friend near Roscommon. She did his washing and mending. As far as we knew, nothing came of it.

He was gone about ten years. By this time he was nearing 50. I was away and married. He spent another 10 years helping my Dad with the farming and chores. I wrote to him occasionally and sent him money for Christmas to buy tobacco. My three older brothers were gone too but our youngest brother, Donald, was home during this time.

My father's health became so poor that he could do little work. Uncle Bob became unhappy because Dad was so easily vexed by him, and still treated him like a little boy. Some deaf friends advised him to apply for work at the Alpena County Farm. He was accepted.

He was the most able bodied man there, and was soon put in charge of the grounds. When we visited him in the summer we found him caring for flowers or running the mower. He was delighted to see us; he always blushed when I kissed him. He was proud of the job he was doing. The inmates admired his lack of concern over his handicaps. The old men said, "He's a great one!"

One fall when he was 72 he fell over dead with a heart attack after an admiring glance at the freshly cut lawn.

As children, we were intrigued by the fact that Uncle Bob could smell rain coming long before we even knew there was a cloud in the sky. He announced it by sniffing and making a motion with his hand like rain dripping. He could feel the ground tremble before the train was due, and always knew if the phonograph was on when he came into the house. He danced a little to the music. We admired him and showed our pleasure by a special facial sign at his talents.

Some of the relatives insisted that he have a very fine funeral. I could not go but spent the time thinking of the jolly times we had together.